Written by: Cait Morrone

Brazil’s enticing charisma comes from the country’s diverse cultural practices, history, architecture, and biodiversity- among other attractions – which brings millions of international tourists each year. Visitors travel through Rio de Janeiro, Salvador, and Amazonian regions among other tourist attractions to take in the culture and tour national parks, beaches, and historical locations. On the outskirts of Brazil’s major cities are the favelas, often depicted as colorful, tightly built communities of low-socioeconomic status.

Brazil’s Favelas

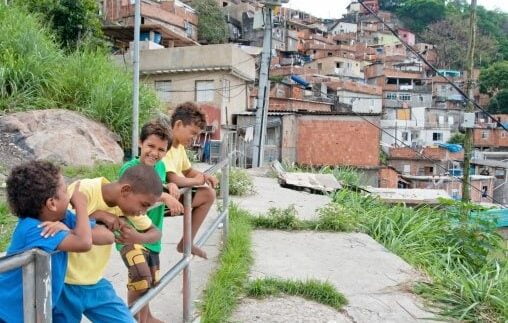

Defined by Britannica and other eurocentric sources as a ‘slum or shanty town located within or on the outskirts of the country’s large cities’, favelas are home to nearly 4 million children. Favelas are often pinpointed as beginning from clusters of homes built from salvaged or stolen materials which developed into large, compact communities that are fortified with brick and cement. Rio On Watch recommends depicting favelas in ways ‘that represent their nature as horizontally structured solidarity communities, which hard-working people have spent decades investing in and building neighborhoods with scarcely a government service’ to instill cultural humility.

However, the Favelas of Brazil have a history far more rich than the negative connotations that come with its definitions. According to Rio On Watch, the term favela originates from the favela tree which was commonly found in Bahia, Brazil. The first favela community was developed by victorious Bahian Soldiers, who settled in favela shrubbery of one of Rio’s hills after the government refused to pay them – naming their hill ‘Morro de Favela’. So, why are today’s favelas associated with such negative concepts and imagery? Rio On Watch depicts four distinct periods within the 1900s which led to the modern stereotypes which are associated with favelas:

- Early 1900’s-1940’s: Favelas were described as ‘the coast versus the backlands’, which was commentary on the ‘opposition between cultured and uncultured’.

- Architects, social workers, and doctors who visited early 1900’s favelas depicted the communities as ‘backwards, unsanitary and oversexualized’.

- These descriptions fueled the undignified view of favelas which guided negative stereotypes and discriminatory connotations about favelas.

- 1940’s – Mid-1960’s: Society began to view favelas as a ‘social problem’ which was impeding the development of Rio de Janeiro.

- A 1950 Census revealed that the majority of favela residents were workers, which ‘somewhat tempered the negative image of the favela’ for the time being.

- 1965 – 2010: Rio On Watch calls this period ‘the moment in which the favela becomes a certified academic research subject’.

- As the population of Brazil and the favelas boomed, non-governmental organizations (NGO’s) began programs for social research about the favelas.

- The bountiful research that was being conducted in the favelas improved social imagery of community life in favelas – ‘ridding them, in academic circles, of their negative research’.

- 2010 Onward: Definitions of favelas began to focus on cultural competence and humility, rather than past negative connotations.

Overall, it is important to recognize that favela communities are not ‘slums’, but are beautiful communities built by self-sustaining persons. Recently, Al Jazeera reported on a home in Brazil’s favelas which won an international ‘house of the year’ prize for the owners innovation and hard-work. This goes to show that homes within the favelas can be as beautiful and creative as mansions in Rio de Janeiro.

Within the favelas is a collectivistic society – led by internal associações de moradores, or residents’ associations – small businesses that support the needs of the community and the people. However, among the rich culture of favelas, there are also high rates of crime and drug trafficking, reports of which play a large part in perpetuating the negative stigma associated with favelas. Criminal and life threatening drug operations are known as ‘factions’ within the favelas, and are a large contributor to the high rate of violent deaths in Brazil.

Historically, children were inserted into the world of drug-trafficking for factions in the 1980’s, and were originally paid with gifts instead of money. Then, with the introduction of the cocaine market, labor dynamics for children in the factions changed, providing fixed salaries rather than gifts. Although the majority of children from favelas volunteer to take on these dangerous roles – every child involved with a faction falls under the Paris Principles (2007) definition of ‘a child associated with an armed force or armed group’ – otherwise known as child soldiers. On the other hand, many children are forced or coerced into drug-trafficking by faction recruiters who strategically target locations where children are most vulnerable and gathered in large numbers.

Why Do Children Join Factions?

Youths’ decisions to join a faction are based on several factors – social, cultural, and economic. The main reason which children resort to drug-trafficking is due to poverty, often dropping out of school to work but unable to find safe employment. In 2019, 1.5 million Brazilian children were not enrolled in school. These statistics showed heavy racial disparities, as the majority of children not enrolled were Black, brown, Indigenous, or Quilombolas (Afro-Brazilian) – making them at higher risk for working with a faction. To add, the increasing number of single families living in poverty has been identified as the fundamental reason that children decide to traffick drugs; especially children of single mothers. Lastly, there are grim cases in which children are forcibly recruited into joining by coercion (ie. threats), offers of money, and/or force (ie. abduction). Every child associated with the factions face dangerous experiences in any position they maintain, either as witnesses, direct victims, or forced participants.

On the other hand, a big contributing factor to voluntary entry of Brazilian children into unsafe work with factions is because of the social status that will be gained. Children in favela communities grow up with drug-traffickers’ consistent presence, which has normalized and idolized drug traffickers to younger populations as people that refuse to struggle during poverty.

Roles of Children in Factions

There are various roles that a child can have within a faction, some inherently involved in drug-trafficking, and others in support functions. The average age for children to join factions is 13 years old; however, they can begin the entry process at only 8 years old. Children typically begin as olheiro’s (watchers), and are motivated to rise in the hierarchy of faction roles, where they gain higher status in the community, and expose themselves to further violence. Table 1 explains the various roles that youth can employ in the faction and the salaries, a fiel (loyal), being the highest position recorded for youth. The duties of a child soldier include protecting the community, alerting others of invasions, or being a bodyguard for important faction members. When a child desires a promotion, they are evaluated based on their skills – including their ability to follow orders, use weaponry, kill, or hold information, as well as characteristics of bravery and trustworthiness. Children in any of these roles are expected to be prepared for lethal attacks from police or rival factions at all times, and weapons are given to them when they show capability of defending the territory. Lastly, children as young as 8 years old, male and female, can occupy support functions, such as cooks, spies, messengers, and sex slaves, and may even be used in horrific suicide bombings and other acts of terror.

Regrettably, due to the high levels of violence experienced in the factions, and the role expectations of children involved, there has been an increasing number of deaths by gun violence among minors in the favelas.

| Table 1: Different Roles Children and Adolescents Have in Factions | ||

| Role | Description/Function | Salary |

| Olheiro / Fogueteiro (Watcher) | Alert the faction of police or other factions’ invasions. Strategically posted to supervise who enters / exits the favela. Often using radios, fireworks, or both to notify others, they are then expected to either help defend the territory or hide. | R$20 to $50 per day (4 to 10 USD) |

| Vapor (‘steam’ seller) | Sells the drugs – favelas can have up to 15 selling points, each with several ‘vapores’ responsible for the selling. The loads are either distributed by the selling managers, and they take shifts, either alone or in groups. | R$3, R$5, or, R$10 per bag sold (0.6 to 2 USD) |

| Gerente de Boca (selling manager) | Responsible for supervising the drugs sales, selecting ‘vapores’ and ‘olheiros’, loading distribution, number of employees, volume of selling, money collection, salary payment and sometimes selling drugs as well. | Not available |

| Soldado (soldier) | Responsible for maintaining order in the community, protection of members and selling points. They are always armed and can also get involved in criminal activities outside the favelas, such as stealing cars, the majority are between 15 to 17 years old. | R$1500 to R$2500 monthly (300 to 500 USD) |

| Fiel (loyal) | Personal bodyguard of important people in the faction. They always carry weapons and are only assigned this position when there is a strong trust bond. | Not Available |

| Source: Children and Drug Trafficking in Brazil: Can International Humanitarian Law Provide Protections for Children Involved in Drug Trafficking? | ||

So, What Can You Do To Help Children in Favelas?

Brazil may appear luscious and its culture exotic, but behind the scenes is gloom and hardship that many of us simply can’t imagine.

If you’re interested in helping children experiencing crises in Brazil, get involved by working with Global Foundation for Girls. You can make a difference in the lives of so many by making a donation, or contacting us to find out about other ways you can get involved to help make change.

Cait Morrone

Program Officer for Brazil and Trinidad & Tobago